Today, many of us feel more connected than ever thanks to technology, after all, knowing what your friend on the other side of the world is eating for dinner has never been easier. However, does that electronic interaction truly make you less lonely? Author Daniel Goleman and emotional intelligence master coach Joshua Freedman discuss why technology is making people MORE lonely than ever.

Even a video call doesn’t fully activate your social brain. As a result, we have become both more lonely and less connected with the natural and physical world around us. The resulting decrease in mental health and wellbeing may seem set in our contemporary culture, but in fact there are concrete ways that practicing emotional intelligence can help us become more connected.

Trapped between The Social Dilemma and the pandemic, we are seeing the effects even more intensely today. Like trying to eat a healthy diet while binging on junk food, our core emotional needs for connection are not being met by “social” networks… or even video. So how can emotional intelligence help us reconnect with ourselves, one another, and the natural world?

Two of the world’s leading experts on emotional intelligence discuss the importance of disconnecting from technology to focus on creating moments of connection.

Joshua Freedman is a Master Certified Coach and leads Six Seconds, equipping changemakers with the skills to grow and practice emotional intelligence in 200+ countries & territories.

Daniel Goleman’s book FOCUS: The Hidden Driver of Excellence (2013) explores the research and practice of attention — which turns out to be of increasing value in our current era.

In-person and electronic interactions feel really different because they send different levels of stimulation to the social brain, “the newly discovered circuitry that lets brains tune in to each other and resonate with each other during a face-to-face interaction,” says Dan.

The full activation of this part of the brain during face-to-face interaction reminds us, “that’s what we were designed for,” Goleman says, “That’s when we have full rapport. That’s when we really connect,” and that’s what can help us move away from loneliness.

Without the Nurture of Nature

So our electronic communication isn’t making our brains feel more connected, but it’s certainly keeping us tied to our screens, and in turn, separated from nature. Josh references The Last Child in the Woods author Richard Louv who “was making the link that today there are so many young people, and adults, who just don’t get near a tree. Perhaps we’re wired to be connected with the natural world… and as we disconnect from nature, we somehow disconnect from our own sense of balance. In turn, we’re not even connected to the people around us, and that leaves us more vulnerable.”

As Dan shares, “the electronic and digital world we’re in today is a kind of cauterized life. In that environment, we need nature more than ever.” But many of us don’t even have the option to “go outside and spend time getting our hands in the dirt,” because of the way industrialization has driven nature and free time out of our societies.

This familiarity and disconnect from both nature and face-to-face interaction, life in this “electronic cocoon,” as Dan calls it, “shuts us down in terms of sensory awareness. We lose some of the richness of the moment and the ability to simply be. It makes us constantly do, whether it’s our work or Facebook.”

We similarly lose our sense of wonder as we grow up, but maybe even more so as we become numbed by the repetitive stimulation of technology. Dan speculates that “as the brain learns more cognitive categories for what’s around us, we tend to habituate more, which is to say the brain closes down to the sensory input because it has an explanatory category for it. The brain tries to economize on energy. One of the ways it does that is by paying the least amount of attention possible to whatever it is that we’re doing. This is one reason that attention, why concentrated attention, actually takes effort to sustain. We exhaust our attention and need to rest, so we tune out.” We are shutting down, struggling to stay present, overwhelmed by so much 2-dimensional sensory input and deprived of the richness of deep connection with humans and other beings. We are lonely.

Escaping the Overload

It can feel hopeless, “here we are in this environment that we’re not actually wired for – we’re alone, we’re out of the sun… Out of human connection. And we’re just so overloaded, bombarded with data,” Josh says. No wonder many of us are distracted, anxious, and depressed. We need some way to ground ourselves, adrift in this turbulent sea of tasks and stimulation with no clear direction. He recognizes that “to cope effectively, we’ve got to explicitly and carefully develop skills for the environment that we’ve created.”

Although we have the potential for more face-to-face interaction in our daily lives, it is much easier to stick with the status-quo of the digital world. Especially when stuck in the rut of poor mental health and wellbeing, it can be difficult to reach out and establish new routes of connection with others. Josh references Dan’s urge for us “to prioritize the people side of our lives,” but that “we also need to have skills for that. If we’re not good at it, it’s harder to actually do it. It’s harder to shift attention, it’s harder to listen, it’s harder to connect, it’s harder to notice your own thoughts and your own feelings. But if you get better at the basic skills, all those things take less effort.” You may have go against your gut, as Dan shares that “in order to change a habit like that, at first it takes huge effort, and it actually feels unnatural. It actually doesn’t feel like the right thing to do.”

Luckily, we have identified these skills, and they can help us improve our wellbeing as we navigate decision-making beyond our technology use as well. Josh is hopeful: “I’ve seen that when people have more emotional intelligence skills, it’s easier for them to make more careful choices.”

Read the interview transcript below for more on creating moments of connection, changing habits, and the divide between our digital world and the natural one.

When we are stuck in a pattern of engaging in the world through devices, we have less connectedness. That dissatisfaction might lead to craving more connection, which pushes us back to our devices. It’s a viscous cycle build into the design of social media platforms to extract attention by fueling dissatisfaction.

The solution is not easy, but it’s simple: Connect for real. Connect with your own feelings. Connect with fellow humans. Connect with nature.

Join IN the world, not just observing it through a phone.

Transcript: Joshua Freedman & Daniel Golman on FOCUS

Part I: September 24, 2013

I asked Dan about the origins of the book, FOCUS: “I’ve always been interested in attention; my earliest research at Harvard was on the retraining of attention to help people recover from stress. But it was only while writing FOCUS that I updated my understanding with the most recent scientific findings that I saw my model of emotional intelligence could be recast in terms of where we put our attention and how.”

We’ve all experienced the link between attention and emotion. If I’m frustrated with a colleague, it’s easy to focus on the ways he’s not meeting my expectations, and my frustration increases. Yet when I focus on the great work we’ve done together, my frustration diminishes. Goleman says this is at the heart of the book:

“In many approaches to EQ, including in Six Seconds’ approach, there is an ingredient of noticing how we notice, of developing new forms of focus. My book FOCUS provides a new framework for understanding why this is so critically important. This book will be valuable for people interested in emotional intelligence because it goes deeply into this essential skillset; a capability that will enhance emotional intelligence, and performance in many professional and personal domains.”

Part II: October 13, 2013

Josh: Dan, I’m excited to continue this dialogue about FOCUS and emotions. From our introductory post, one of the members mentioned that sometimes our focus creates a sense of wonder.

Sometimes we’re engaged in the world – like children, fully immersed in the moment. What is going on there when we see with childlike wide-eyed wonder?

Dan: Children have a richer sensory experience of the world than do adults. It’s less filtered. They have fewer mental models to pre-explain or to abridge what’s being seen. I think I remember from being a kid experiencing a sensory world that is far richer than what we see as adults. And I think that allows more moments of wonder.

And it may be that – this is just speculation – as the brain learns more cognitive categories for what’s around us, we tend to habituate more, which is to say the brain closes down to the sensory input because it has an explanatory category for it. The brain tries to economize on energy. One of the ways it does that is by paying the least amount of attention possible to whatever it is that we’re doing. This is one reason that attention, why concentrated attention, actually takes effort to sustain. We exhaust our attention and need to rest, so we tune out.

Time to Wake Up?

Josh: I saw a study the other day that said that something like 50 percent of the time as adult, we’re just on autopilot. Actually I suspect it’s more like 95 percent of the time, we’re going through the motions of our days without any real attention and focus. While that’s efficient, it makes it difficult to make careful choices, to respond instead of react, to innovate, or to really solve problems.

Dan: I think you referring to that incredible study by Killingsworth and Gilbert at Harvard where they had people carry iPhones with an app that called them at random points of the day and asked them to say, “What are you doing, and where’s your mind?”

The study showed that, on average, people’s minds are wandering close to 50 percent of the time, no matter what they’re doing (except if they’re making love, it’s not wandering much at all). If they’re on their way to work or they’re at work or they’re sitting in front of the computer, it’s wandering a massive amount of the time.

Josh: Now, there’s an experimental design issue here. When is your phone ringing? And who’s bothering to answer it if you’re making love?

Dan: I know! Those subject must have been really dedicated to the study.

Getting Back into Focus

Josh: Whatever the percentage is, I think we all know that we go through huge parts of our days without actually paying attention to what’s going on. We’re just getting to the next thing. It’s actually stunning to consider – am I really living my life?

I suspect this gets worse as we increase the number of tasks on the “To Do List,” and the number of messages coming across our desks. As demand increases, unfortunately, our focus decreases. Does that seem reasonable?

Dan: I think two things are going on, Josh. One is that there are two main systems for attention. One is top-down. This is what we think of as conscious, intentional focus. The other is bottom-up. That’s life on autopilot.

The brain is actually designed to put most of what we do routinely on autopilot. It’s that energy conservation principle that I mentioned before. Autopilot, in that sense, is not necessarily a bad thing. You don’t want to have to think about every step in turning on your computer or every step in making your coffee in the morning or brushing your teeth.

Josh: It’d be really inefficient.

Dan: Exactly. There are ways to make ourselves more conscious. That’s what mindfulness meditation does. But you want to be selective in how you use mindfulness. The brain does not want to be mindful in ordinary life all the time, contrary to what a lot of mindfulness teachers will tell you. Our brains aren’t wired that way. It takes a great deal of effort and attention.

What’s powerful about being mindful, is we de-habituate life itself.

Josh: Where “De-habituation” means waking up, living on purpose?

Brain vs. Computer

Dan: Yes. De-habituation means that you get more of those moments of full sensory experience – more wonder, if you will, more fullness of the moment. In an Eckhart Tolle sense, more, “in the now.”

When you’re talking about the barrage of distractions we face at work, I think that’s something really different. There are a set of challenges we face in maintaining a full, intentional, focused awareness on our work. The tasks we’re trying to get done, the work we’re being paid for, the work we feel is meaningful, or the work that has some purpose.

That kind of attention is under more challenge than ever in human history – I mean, many of us work at a computer. A computer is a machine that is designed both to help us focus on our work and to distract us at the same time. We have pop-ups, you can always go on the web, and the big challenge is to be able to notice when your mind has wandered – the study said an average of 50 percent of the time, but most at the computer.

One key: notice when your mind has wandered and then to detach from where it’s wandered to, and bring your mind back to the point of focus.

Well, that happens to be the “basic move” in most meditation. In mindfulness of the breath, for example, you make a contract with yourself. “I’m going to focus on the breath and keep it there. And when my mind wanders, and I notice I’ve wandered, I’m going to bring it back.” That is the essence of the practice, and it’s the mental equivalent of going to the gym and going on a Cybex machine and doing repetitions to work a muscle. The more you do that, the stronger the circuitry from noticing the wandering, detaching, and moving it back gets.

This is the work done by Wendy Hasenkamp, who’s now the research director of the Mind and Life Institute. When she was at Emory, she did brain imaging studies of people trying to keep their mind on one thing and how it wanders off. She identified what circuits are aroused as you’ve noticed you mind has wandered, what fires as you detach from wandering, and how the brain works as you bring it back to point of focus.

Those are three different interacting sets of circuitry. The more you practice that move, the more richly connected those circuits become, and the larger the space they take in the brain – in other words, they get stronger.

And I think today we need that kind of mental exercise, more than ever in the past, because we’re challenged by more distractions in more insidious, elegant, seductive ways than ever before in human history.

Josh: Just to recap the three steps to practice:

- Notice your mind has wandered – “Hey, I’m on Facebook again.”

- Detach from the new focus – “Whoops, I better stop reading about my friend’s weekend.”

- Refocus – “Time to get back to writing!”

This reminds me of a shift from external to internal focus. We had a conference in June at Harvard; one of the speakers was Mary Helen Immordino-Yang — she’s a neuroscientist studying learning and emotion. Her talk was fascinating; her research shows that essentially we have a brain system that is activated when we focus externally and a different brain system that’s activated when we focus internally, and that those two are anti-correlated.

Immordino-Yang’s research shows that in order to focus externally, we suppress that internal reflection. And in order to focus internally, we suppress that external focus. I think that’s intuitively obvious once you see it, but the idea that these two brain systems are actually different areas in the brain, really only one can be active at once, I think tells us something about this whole issue of focus.

Dan: This phenomenon of anti-correlation of attention circuits is very important. It helps us understand what it takes to get work done well. The system for monitoring he mind, that is the inward awareness system, is different from the system for full external sensory awareness. You’re either in one frame of mind or the other.

Josh: And, in a way, they’re opposed.

This is Your Mind on Stress

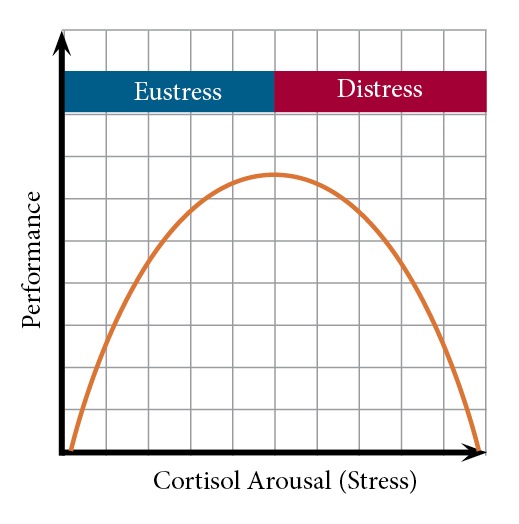

Dan: Exactly. This ties to calming and stress. There’s an upside down U that describes the relationship between performance and cortisol levels (which is the stress hormone). When people are very bored, they’re at the lower end on the left side of that upside-down U. When people are fully absorbed, when they’re in flow, they’re at the optimal point at the top of the U. And when they’re overstressed, they’re on the right side, where performance is poor and cortisol is very high.

Josh: So when we’re bored, performance is also low. As we go from boredom up to focus, we experience Eustress, or positive stress, and performance climbs. Then if stress goes too far up, we enter distress – and then performance plummets again.

Dan: You got it. That’s the U. So each of those points describes a different neural circuitry. When you’re bored, you’re actually in that mind-wandering space, and there’s circuitry for mind wandering. For those who like details, this circuit is called “medial.” The medial zone is, in a sense, the brain’s default. When we’re not doing anything in particular, we activate that circuitry. When we’re fully absorbed, when we’re doing work we love – we’re in another set of circuits that have to do with full, concentrated focus. Then when we get stressed, the amygdala activates and other distressing emotions arise. The circuitry for that distress is taking attention from the task and focusing it elsewhere, taking us away from the work we have to get done.

So performance plummets when the mind is wandering, or when we’re overstressed, because each of those circuits takes our attention away from the job. They take us off the top of the U, that point of full focus on the work at hand. If you can be mindful, you can notice where your mind is and bring it back – whether you’re overstressed or whether you’re under-stressed.

Josh: Unfortunately, it doesn’t take very much to get off that peak performance point. I’m just thinking back to what you said about the computer. Several times this year I’ve decided it’s time to be editing my book about fatherhood. I sit down to start editing, and I notice that I’m on Facebook again. It’s not a huge amount of stress to tip me off the U!

Dan: No! And, to make matters worse, on Facebook you get all of these little hits of oxytocin or other reward chemicals when the brain says, “Oh, they liked that thing I posted.”

Josh: “They like me. I belong.”

Dan: Exactly. And when you’re all alone editing your book, you’re not getting those hits. So it’s very seductive. This is why I say it’s kind of diabolical that the same device we use to get work done is also the one that seduces us away into distraction, which is another reason we need more ability to focus when we want to.

Part III: October 28, 2013

Nature in Focus

Josh: Another member posted a question about nature. I’ve certainly experienced – even when I’m just out in the garden, but certainly when I’m in high, wild places, I have a sense of my mind being more open. I feel more tuned in to the world. I told you my son was at a camp where he spent two months totally unplugged – not even a flashlight. There’s this awakeness that he experienced. He felt connected. What’s going on with nature?

Dan: I think it’s wonderful that he had that experience. I think every kid and every adult should have it regularly. When we live in this electronic cocoon, I think it shuts us down in terms of sensory awareness. We lose some of the richness of the moment and the ability to simply be. It makes us constantly do, whether it’s our work or Facebook.

Online Meetings and the Social Brain

Josh: In Social Intelligence, you describe that the social brain is not actually activated when we’re communicating electronically. I recently came across an article I wrote back in 2007 on the emotional challenge of teens’ increasing disconnection, called “Alone in the Parade,” and the problem has escalated dramatically since then.

Even in this conversation, my understanding is that our social brains are only partially activated.

Dan: The social brain, the newly discovered circuitry that lets brains tune in to each other and resonate with each other during a face-to-face interaction – that’s what we were designed for. That’s when we have full rapport. That’s when we really connect. And electronic media – even a Skype call, a video call, don’t give us the same full richness that you get face to face. You don’t get all of those signals coming in.

A phone call gives you voice alone, so there’s less data, less social brain activation. And the worst is email, where you get zip of the nonverbal cues that give nuance and context to the interaction. So you get only the words, which are the least part, in some sense, the least part of the human communication.

Coping in an Un-Natural World

Josh: So going back to nature – I remember reading The Last Child in the Woods – Richard Louv’s book from 2005. He talked about Nature Deficit Disorder. Did you pick up any of that?

Dan: Yes. The electronic and digital world we’re in today is a kind of cauterized life. In that environment, we need nature more than ever. We need those two months off-grid that your son had. I think it’s wonderful.

Josh: Louv was making the link that today there are so many young people, and adults, who just don’t get near a tree. Perhaps we’re wired to be connected with the natural world… and as we disconnect from nature, we somehow disconnect from our own sense of balance. In turn, we’re not even connected to the people around us, and that leaves us more vulnerable.

Dan: I totally agree. I wouldn’t add a thing to that.

Josh: So again, coming back to your point earlier: Since we’re living in these electronic, inundated times, it becomes even more important to learn about focus. We could go outside and spend time getting our hands in the dirt, but in some places in the world, that’s tough. So here we are in this environment that we’re not actually wired for – we’re alone, we’re out of the sun…

Dan: Out of nature…

Josh: Out of human connection. And we’re just so overloaded, bombarded with data. To cope effectively, we’ve got to explicitly and carefully develop skills for the environment that we’ve created.

Dan: I think that FOCUS and thinking about focus is so timely. Another example: it’s become insidious how our electronics impede face-to-face communication. I saw a little toddler in her mom’s arms the other day, desperately trying to get her mom’s attention. Mom was texting someone, ignoring the baby. Couples out at a romantic restaurant – they’re both looking at their tablets or phones. Families – the same. Everyone’s looking at a screen and not at each other. And because this has become the new normal, we need to take active steps. We need to be sure we do experience nature regularly, that we experience each other fully, that we get away from the lure of our Facebook, our Twitter, our whatever it is, and do what we choose do which is enriching. And it might be getting your work done. It might be hanging out with someone you love.

Josh: And feeding our emotional selves is really important. I want people to understand that that’s not just “nice to have” emotional nourishment.

Creating Moments of Connection

Dan: I agree, it’s a necessity – particularly, for example, in couples. I know an executive – high-powered job. A woman in New York, she says, “When my husband and I come home, we put our phones in a drawer, and we don’t take them out till after dinner, because we want to actually spend time with each other.” I think you have to be more intentional today.

Josh: I was noticing that I would be so caught up in the computer, I wouldn’t pay attention when my wife would come into the office. You know Anabel Jensen, the President of Six Seconds. One time Anabel and I were talking about this, and she suggested, “As an experiment, when Patty comes in, why don’t you just try getting up from your desk for a minute?”

Dan: That’s a very good idea. It reminds me of an article that was in the Harvard Business Review a while back called “The Human Moment.” It says, “If you want to have a moment where you really connect, which are the moments that are the most effective for leaders, you have to turn away from your screen, ignore your digital devices, stop your daydream or wherever your mind was, and pay full attention to the person you’re with.” That’s the first step in rapport.

What Anabel suggested is very wise advice. And there’s another thing. My wife and I now have an implicit agreement that when one of us is emailing or looking at Facebook, and the other is not, we’ll tell the other what we’re doing. That is, we’ll have joint mutual attention, which is a step better than just being ignored.

Josh: Right. So while you’re not fully engaged with one another, you’re making a commitment to connect at least a little.

I find this challenging because I’m a pretty task-oriented person, and I’m somebody who has a huge, long to-do list. While I can notice when one of my employees or one my family members wants attention – it takes an active will. It takes effort to stop focusing on tasks and switch to connecting with people.

Dan: That’s right.

Josh: Unfortunately, I’ve experienced that it’s all too easy to forget the importance of that human interaction.

Dan: Which is why we have to make an effort to remind ourselves that it matters. If we tell ourselves, “Oh, an interruption,” people become a bother rather than the point of it all.

Josh: And a leader’s job is really about people, not about task. And we forget that.

Dan: Leadership is connecting to people, absolutely.

Developing Skills to Connect

Josh: One more topic related to your new book, and the work that we’re all doing: If we can get better at these skills, it becomes easier.

I’ve seen that when people have more emotional intelligence skills, it’s easier for them to make more careful choices. You mentioned we have to prioritize the people side of our lives. But we also need to have skills for that. If we’re not good at it, it’s harder to actually do it. It’s harder to shift attention, it’s harder to listen, its harder to connect, it’s harder to notice your own thoughts and your own feelings. But if you get better at the basic skills, all those things take less effort.

Dan: This has to do with the science of habit change, particularly emotional habit change — and then a personal habit change. My wife just wrote a really good book about this called Mind Whispering.

Josh: Great title.

Dan: I recommend it. What she points out is that when we get into the habit, for example, of being glued to our devices or to our work and ignoring people, that has become a default option in the brain.

Josh: Right. We make a “new normal.”

Dan: Exactly. And in order to change a habit like that, at first it takes huge effort, and it actually feels unnatural. It actually doesn’t feel like the right thing to do. So you need to make a deal with yourself, a contract, that I’m going to do it anyway. The more you repeat it – the easier it gets.

The example you gave earlier is a great contract to have with yourself: “When someone comes into the room, I’m going to turn away from my computer and pay attention to them.” If you make that deal with yourself, and you do it at every naturally occurring opportunity, at first it’s going to feel, “Oh my gosh, why are they bothering me?” And then it’s going to start to feel easier. And then it will become the natural thing that you do. That’s a neural landmark. It means that you have rehearsed the new habit enough that the connections in the brain for the new habit are stronger than for the old habit. And that’s what you’ll do naturally now. So it takes practice, but it’s certainly worth it.

Josh: We should talk more about this process, but maybe we should save that for our next conversation! I’m going to go check out Tara’s book now — I found her previous book on Emotional Alchemy incredibly valuable — in fact, I was just talking about this last week in a course. So — more reading!

Dan: Excellent. I’m looking forward to the next installment.

Stay up to date!

Want the latest updates and articles on emotional intelligence, including this quarter’s posts about the digital era? Sign up for our newsletter. It’s once a week and you can unsubscribe anytime, but I think you’ll find it to be refreshingly simple, practical and scientific.

- Enhance Emotional Literacy - July 13, 2023

- Plutchik’s Wheel of Emotions: Feelings Wheel - March 13, 2022

- Technology Loneliness: EQ Tips from Daniel Goleman - October 24, 2020

Thanks so much for sharing this post! Electronic communication is our new reality in this pandemic time. And I agree that new difficulties arise.

As life becomes more complex, and smart phones, social media and technology distract us from learning important social skills, connection and associated values, who takes responsibility for advising governments and regulators on what level of technology usage and what behaviours prevent addiction and encourage the development of important life skills like delaying gratification? It would appear to me that as proponents of the benefits of emotional intelligence, that we need to be a lot more vocal and assertive in persuading the powers that be of the detrimental impacts of digital technologies on development. Every day I am witness to people who are suffering through a genenal lack of awareness, trust and resilience that comes from learning Ei and the associated life skills.

How do we make more of an impact Josh?

I totally agree we need to create a habit when we are with others physically. Yet the dilema we have is that knowledge education is through technology and i myself am moving to coaching and delivering webinars on line to save the travel. Any comments here.

Josh thanks for this inspiring interview. I wanted to read it in preparation of our next EQ Cafè Connection. This Challenge is so timely.

Thanks waiting to Hug and look you in the real life:-)

Josh thanks for this inspiring interview. I wanted to read it in preparation of our next EQ Cafè Connection. This Challenge i so timely.

Thanks waiting to Hug and look you in the real life:-)

can anyone guide about the best institutes offering certifications in emotional intelligence? What is the best book to get an initial knowledge about this skill? Thanks

Greatly insightful! Thanks for directing attention to an issue that is so central in each of our lives.

I just managed to read through the 3 parts of on this dialogue and I find it totally insightful and applicable to this life that we have in this generation.

I guess its not only Facebook that is a great distraction but any other social media or electronic devices. Its totally frustrating when you go for a gathering and find everyone using their phones trying to “check in”, “tweet”, uploading photos, “adding friends” or mass spamming “selfies”. when their attention suppose to be on each other or at least a human being. We are at this time and age whereby one “cannot live” without a phone, mobile devices, computer and internet. We feel so crippled by it. What’s our very priced possession is also shackles to life.

You are likely observe the following here in Singapore:

Instead of enjoying your meals with your family and friends, you can commonly people busy taking photos of food, editing and posting them on Facebook, Instagram or other social media, hoping to achieve high number of likes, to the extend of “addiction”?

In some cases whereby people act or talk differently when they text or converse over mobile devices in comparison to face-to-face meet ups. People start to develop this level of social awkwardness, which to a huge extend, its actually troubling.

What’s more troubling is when parents keep their children “entertained” through electronic devices and games that are supposedly “educational”. The kids want to use these devices so much that their attention and focus leave their parents for the “robots”. They are awkward with the nature or the natural environment, to a certain extend, fearful of them. Kids starts to know a lot but stop experiencing.

Thank you for the thought-provoking discussion. If we continue down this path, we will become like the electronics that control our lives – machine like. If we don’t take the time to connect with each other face to face, we will lose our ability to connect and interact. It occured to me that each night when I take my iPad to bed (to unwind), I am losing the greatest opportunity to connect with my husband of 32 years. Yet, I am the first to complain that we are “distant” at times. Time to develop new habits!

Josh,

This article made very interesting reading.Dis-connecting to connect gives us a chance to prioritize what we want for the moment. I loved the term “contract with yourself”, the most needed contract to understand the evolutionary purpose of our emotional brain. Living in a techno savvy time, where relationships are at a virtual level, people find it so difficult to connect without a device!Hence, dis-connecting with a device and connecting with REAL self and REAL others will help in coping in this un-natural world where the skills of Emotional Intelligence have to be understood, learnt and practiced.

It’s really awesome article …….. it’s really eye opener for me…

while reading the article I was actually visualizing all my actions, behavior.

In one of the paragraph its truly said that – we have to be more intentional today.

Josh,

As a professional and SME in Disaster Preparedness and Training, innovation and technology are welcomed adjuncts to what we commonly refer to as; Interoperability. Training citizens to BeMorePrepared is a lifelong journey. Factoring in EI and change, we have our work cut out for us! Coaching individuals with regard to preparedness brings with it the great reward of being able to reduce the anxiety that often accompanies the thought of being affected by a catastrophic event. Those of us, especially you, who live to bring order and reason to the unknown, are truly change agents.

That’s one of the driving factor for demand for coaching. Essentially, coaching is about building powerful partnership with the client and what client really benefit most is the deep connection with someone who believe in them. What is often holding us back is not a competency issue. When we are able to give people the positive unconditional regard, you can be sure to see them thriving. This is fundamentally a EQ Competency – social connection with other bring in a meaningful way.

The endless parade of things to do that accounts for every moment of the day doesn’t leave time for creativity. The most linear of environments has rich opportunity for creativity where the juice of it all resides. We all need space to work ON our business, life, relationship or any other segment of our lives while we’re working AT those same things.

Hi Errol – I so agree. Maybe we also need to be IN our lives and work too… Work at, work on, and be in… and we typically let the first one completely overload the others. I’m in a frenzy right now trying to finish “stuff” before leaving on a trip, and coming right up against this. “Working hard at” is such a powerful state, yet it’s a trap to stay there.