The plane I am sitting on bumps and shakes.

I look out the window; we are so perilously far from sturdy ground. The familiar sense of fear grabs ahold of me. My heart rate speeds up. Cold sweat pricks my skin. My stomach drops. These sensations cry out for me to pay attention and DO something, so I do.

Knowing that I am the author of this story, I decide to act instead of react to my fear. My sweaty palms wound tightly together, I desperately focus on my deliberately slow breathing. In. Out. In. Out. I repeat my mantra for times of fear over and over again: “This is how it feels to be alive.” I do feel alive; my emotions are so loud and textured that they couldn’t possibly be ignored. My body still rings alarms of danger, but my mind and soul understands this situation for what it really is. This is an opportunity for acknowledging fear as a rich reminder of my precious life.

Rewind to a year ago. I am sitting on a plane, and we hit turbulence. I feel the same trappings of fear — quick heartbeat, cold sweat, shallow breathing. I am still the author of this story, but I am far from aware of this. I react unconsciously out of fear. My thoughts tumble mindlessly into nightmares of my death. I allow every bump and shake to throw me more deeply into my story of terror. Every cell in my body seizes with fear, and my mind fuels the flames with scripts upon scripts of helplessness.

I am spun out on fear; no part of me is any longer rooted to myself. I do not feel healthy, and fear is ruling my body. I have become fear.

What has changed between these two scenarios, just a year apart?

Practicing emotional intelligence on a plane has become my habit.

Writing a new habit or erasing an old one can be among the most rewarding benefits of practicing emotional intelligence. Emotional intelligence gives us the tools to recognize our patterns, find the strength to change them, and identify our powerful motivations for doing so. Even still, transforming a new way of life into a habit is challenging. Ask the 92% of people who break their New Year’s resolutions every year. Luckily, we are not alone in this challenging process. Neuroscientists, social psychologists, and behavioral analysts have gone before us to help us demystify the process of our rewriting habits.

Defining Habits: Is my social media use a habit?

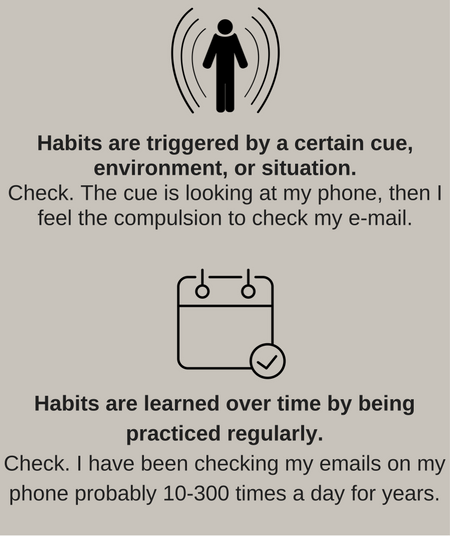

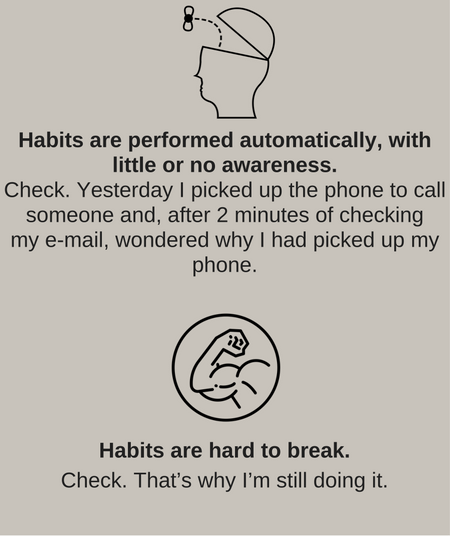

Let’s begin by defining habits. I’ll offer up one of my dirty habits for our consideration. I can’t pick up my phone without checking my e-mails, text messages, or Facebook. Believe me, this is not the most unsavory habit I practice, and I also suspect I am not alone. It is so compulsive; I do it without thinking. The phone is in my hand, and, before I know it, I have pressed refresh on my e-mails. When I do become aware of the phone in my hand, I feel kind of disgusted with myself. Is this really how I want to spend my one wild and precious life — compulsively pressing refresh on my screen?! Needless to say, checking my phone is a habit. Or is it? Let’s find out.

Neuroscience defines habits as having this set of characteristics:

Do you have a habit in mind? How does it check out with these characteristics?

Now that we’ve defined the habit, shall we go about breaking it?

As it turns out, if I really want to ditch my social media habit, I should go on vacation. Why? The answer lies in the habit loop, a behavioral pattern made famous by Charles Duhigg, author of The Power of Habit. The habit loop consists of three parts: the cue, the behavior, and the reward. I invite you to think of a current habit that would make your life better by being broken. As we go through the process of the habit loop, you can think about what the cue, behavior, and reward is of your particular habit.

First, the cue. The cue of a habit is the trigger. It is the stimuli that precedes partaking in the habit itself: the environment, the emotions, and the visuals that tell your brain to go into the automatic mode of performing a habit. For my phone habit, I know that I only get “plugged in” to my social media when my phone is in my direct line of sight. What is the trigger to your behavior?

The second piece of the habit loop is the behavior itself. Clicking on the Facebook app. This part is done without thinking. Literally, the activity in our brains switch location once we partake in a habit; the conscious, decision-making prefrontal cortex goes dark and the unconscious, habit-performing basal ganglia lights up. For my habit, this is signified by the moment I click on the e-mail app on my phone.

Lastly, the reward. There is always some kind of positive feedback from partaking in a habit. For my habit, the reward is my brain being inundated with dopamine upon receiving contact from someone else. This reward that tells my brain, “Great. Let’s do more of this.” What is the reward of your behavior? Why does it feel so good? Identifying the reward helps us to change the behavior.

So why should we all go on a habit-breaking vacation? It turns out vacations really do produce better habit-breaking results. Why? If we think of the behavior loop as a sandwich, the “bread” (the cue and the reward) are the ones we can change, the “filling” (the behavior) is automatic. When we go on vacation, the “bread” gets switched up. The view is different, we get up at a different time, we get mood-boosts throughout the day that aren’t tied to our habits. Our environmental and reward patterns are so different from our regular life that we are able to chip away directly at the center of our sandwich: the habit itself.

I know we can’t all drop our commitments and go on vacation every time we want to break a bad habit (sadly). Instead, can learn about the conditions of “vacation-ness” and apply them in our daily lives? If we examine the habit loop, perhaps we can identify changes we can make around our cues and rewards.

There is another trick to unsticking a habit, explained below: Shifting the emotional story. For this, too, having awareness of the neuroscience of habits, we open ourselves to transformation.

If we think back on my fear of plane turbulence, we will notice that I did not simply lose my fear of crashing. In fact, my fear of crashing is still deeply intact. It is calmed, though, because of the new habits I have installed in my brain and body. I relax my body through taking deep breaths. I focus my mind away from doom by repeating the mantra, “this is how it feels to be alive.” I recognize my raw emotions as a reminder that life is precious. My new habits are simply layering over the old ones, but, in that layering, my old habits are becoming much less intense.

I allow my feelings of danger to direct me toward the inevitable truth that I will one day die. Instead of letting this fact inspire doom, though, I let this be a reminder of how precious my life truly is. By changing the emotional story, I change the context of the “habit loop” – it’s a kind of mental vacation even if I’m not at the beach.

What is a new habit you can steep into an old one? Using what we’ve learned about the habit loop, we can apply a lot of the cue/reward systems to bolster healthy, upcoming habits. What kind of existing cues for old, worn habits can be repurposed for your healthier habit? Does your new habit have a built-in reward, or can you create one that will prime your brain for repetition? In the midst of this process, can you use the tools of emotional intelligence to offer yourself compassion when you fail, and fuel from your noble goal when you lack motivation?

Let’s chat in the comments about the habits we want to write or erase. Are you wanting to break a bad habit, make a new habit, or do both? We have a whole community of EQ behind us, so let’s do this together!

- Identify Your Most Fulfilling Career: A Step-by-Step Guide for Women - March 21, 2022

- POP-UP Festival Partnership with AEON Corporation - March 9, 2022

- 3 Interview Tips for Women from an Executive Emotional Intelligence Coach - February 9, 2022

There are lot of things we do daily, without any reason. I have a habit of biting my nails especially in leisure time…

Good suggestion from the author. Need to try.

Great article! I’m a long time smoker who knows my life will change for the better if I quit. I’ve tried to quit many times, with some success. It’s no doubt my habit of unconscious choice when life gets stressful.

I just booked a Caribbean vacation for a month from now. I was already thinking this could be a great oppty to break this horrible habit, again. Thanks for the confirmation that there is wisdom in this strategy.

All the best!

Jen

Have a fabulous adventure of change!

I find that breaking habits is a practice. They don’t have to be bad habits; they can merely be repetitive behaviours that close us off, such as driving the exact same way to and from work, when there are so many other routes. Changing habits causes attentiveness, which fills me with the reward to novelty.

I love this — it’s about being awake in our lives!

This is an excellent way to explain the problem of getting rid of bad habits. Appreciated so much!