Would you say that you think more clearly and wisely about other people’s problems than your own?

Whether they know it or not, the answer for most people is yes, according to recent research published in the Journal of Psychological Science. This phenomenon, known as Solomon’s Paradox, is widespread – we tend to reason more wisely about other people’s problems than our very own. And while researchers have proven this is a real tendency, they have also found a simple, practical technique to reverse it – and take advantage of the wisdom within.

So how did researchers prove that this phenomenon is real? And how can we apply the wisdom that comes naturally when we think about others’ problems to our own lives?

Let’s take a look at the research and the practical technique the researchers found.

King Solomon, the third leader of the Jewish Kingdom, is thought of as a sage and a man of great wisdom. People traveled great distances to seek his counsel. But what’s not remembered quite as well is that his personal life was not so pretty. He made bad decisions repeatedly, had uncontrolled passion for money and women, and neglected to instruct his only son, who went on to ruin the kingdom. Hence the name, Solomon’s Paradox. Plenty of wisdom for others; but not for oneself.

But is this really true of us living in the 21st century? Do we really think more wisely about other people’s problems than our own?

Igor Grossman, a psychological scientist at the University of Waterloo in Ontario, set up a series of experiments to prove or disprove Solomon’s Paradox – and see if there is anything that can be done about it.

In a fitting ode to King Solomon, a serial womanizer who had hundreds of wives and concubines, the experiment looked at infidelity and the wisdom of people’s responses to it.

Solomon’s Paradox: An Infidelity Story

Grossman first set out to establish the validity of Solomon’s Paradox. Grossman defines wisdom as “pragmatic reasoning that helps people navigate life’s challenges. This requires transcending one’s egocentric point of view – recognizing the limits of one’s own knowledge, taking others’ perspectives, and seeing circumstances in flux.”

To test people’s wisdom, he ran an experiment with a cohort of people in long-term romantic relationships. He split participants up into two groups. The first group imagined that it found out that their partner had cheated on them. The second group imagined that their best friend’s partner had cheated on their best friend. Then everybody answered a series of questions about the future of the relationship that measured these key components of wisdom: the ability to take others’ perspectives, recognize the limits of one’s knowledge, and search for compromise.

And what did they find?

Sure enough, the group that imagined their best friend being cheated on scored much higher on these measurements of wisdom than the group who imagined themselves being cheated on. They had a clearer sense of self-awareness and a better ability to empathize; they could step back from the situation and think about it from a wider perspective. They were, in several key ways, more emotionally intelligent as it related to the situation.

Having proven Solomon’s Paradox, researchers took it a step further, asking themselves: Is it possible to help people distance themselves from their own problem and think about it like they would a friend’s problem?

.

Solomon’s Paradox: Can You Spare Some Wisdom for Me?

To test this, Grossman and his colleagues ran the same experiment as above – but with a twist. The group that imagined that they had been cheated on got broken up into two subgroups. They instructed the first group to think about being cheated on from a first-person perspective, to really immerse themselves in their thoughts and feelings. This group asked themselves questions like, “Why am I feeling this way? What are my thoughts and feelings about this?” But the other group thought about being cheated on from a third-person perspective – like they were looking in on themselves and their relationship. They asked questions about themselves in the third person, like, “Why does he or she feel this way?”

And what did they find? The third-person participants scored higher in wise reasoning than those who thought about it from the typical first-person perspective. In fact, those who distanced themselves from their own experience were indistinguishable from those who pondered their friends’ situation in the first experiment. Psychological distance, it seems, is the tonic to Solomon’s Paradox.

Maybe King Solomon should have pictured himself traveling a great distance to seek advice from a wise sage. According to this research, that’s all he needed to do to tap the wisdom within.

Grossman and his colleagues decided to tackle one more question related to wisdom: Would age make a difference in terms of these experiments’ findings?

Does Wisdom Come with Age?

Grossman and his colleagues wanted to look at one more aspect of wisdom and Solomon’s Paradox. Do people gain wisdom with age? Older and wiser, as the saying goes?

To test this, he recruited a young (20 to 40) and old (60 to 80) group of participants. He gave them a different kind of scenario to consider – instead of infidelity he had them imagine a different kind of betrayal by a close friend or family member. Just like in the other studies, some participants thought about this betrayal from their own experience and others pondered it as though it happened to someone else. Then they answered questions to assess their wise reasoning about the situation.

Contrary to popular belief that wisdom comes with age, the older and younger participants were equally as likely to reason wisely about the situation – and equally as susceptible to Solomon’s Paradox. And they were just as likely to become wiser by using the self-distancing techniques. The older and younger group were, by and large, indistinguishable.

This is a similar finding to Six Seconds’ research into age and emotional intelligence more generally. Using the SEI, an emotional intelligence assessment, they found a very slight correlation between age and emotional intelligence, meaning that while older people were slightly more likely to score high on EQ, it was not a very strong correlation.

Grossman’s research also points to another fundamental truth supported by other research: emotional intelligence skills are learnable. Taking others’ perspectives, increasing self-awareness, and the ability to connect present decisions with bigger goals are all learnable skills that are highly correlated with personal and professional success. Grossman’s self-distancing technique is one of many tools that people use to enhance one part of their emotional intelligence.

Want to learn more about practicing emotional intelligence? Join us today.

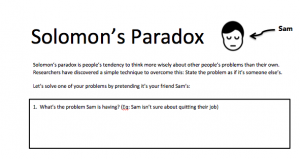

Want to try it out for yourself? We created this worksheet to help you imagine a problem as if it’s someone else’s. You can download it free by filling out the form.

What’s new in emotional intelligence?

From Enemy to Ally: How Eric Pennington Changed His Relationship with His Own Emotions – and Found His Life’s Purpose

How emotional intelligence helped Eric Pennington transform corporate life setbacks into strengths – and find purpose in both work and life.

Helping Others Achieve Overall Well-being and Healthy Connections: How Emotional Intelligence Guided Pamela Barker’s Career Path Growth

Pamela Barker’s journey began with healing bodies, but it was her discovery of emotional intelligence that unlocked her true purpose: helping others achieve overall well-being and healthy connections. From her days as a physical therapist to becoming a passionate EQ coach, Pamela’s story is one of transformation, resilience, and the power of connection. Her experience shows that real change starts from within.

Harnessing Emotional Intelligence: How Sara Canna Supports Employees and Transforms People’s Lives at the World Health Organization (WHO)

Emotional intelligence is more than just a buzzword—it’s a transformative tool that can reshape how we navigate challenges, build relationships, and thrive in demanding environments. Discover how Sara Canna brought EQ to the World Health Organization, empowering employees to manage change, stress, and personal growth.

From Corporate Consultant to Coach: Elise Jones’ Emotional Intelligence Journey-Voices from the Network

Elise Jones transformed her career by embracing emotional intelligence, shifting from a corporate consultant to a passionate EQ Coach. Through authentic connections, she found deeper fulfilment, proving that strong relationships are key to a happier, more meaningful life.

Want to Manage Your Emotions More Effectively? Find Time to Journal About Challenging Experiences

Daily journaling to reframe unpleasant events can significantly reduce depressive symptoms, lessen stress, and increase life satisfaction.

A Journey through Empathy & Optimism: Amy Jimison in Voices from the Network

When you feel stuck and can’t see a way out, how do you navigate change? Certified Coach and leadership expert Amy Jimison shares her approach.

- Pursue Noble Goals in the Six Seconds Model of EQ - July 29, 2023

- Increase Empathy in the Six Seconds Model of EQ - July 26, 2023

- Exercise Optimism - July 24, 2023

To me this is an answer to my long time struggles with navigating through the maze of my own life successfully, I have helped others significantly not knowing I can apply the same on myself. Thanks

Worksheet does not download

Hi Hana, Thank you for letting us know! It should be working now.

Hi Phillip

Enjoyed the article thank you

The worksheet does not seem to download

Hi Glenn, thank you for letting us know. It should be working now. Thank you!

Hi Philip! There was a technical hiccup, and thanks for alerting me to it. It’s been fixed, and now the link takes you to the Solomon’s Paradox Worksheet. Let me know if you have any more trouble!

I have extremely enjoyed your article. My thumbs up. Well done!

Thank you very much, Enos! It’s interesting stuff, huh?

Terimaksih atas ilmu pengetahuannya

The worksheet seems to load as a window within this window and the “worksheet” is a graphic image of self awareness tips, not like the image you showed above.

Is there a technical hiccup here?

Hi Philip! There was a technical hiccup, and thanks for alerting me to it. It’s been fixed, and now the link takes you to the Solomon’s Paradox Worksheet. Let me know if you have any more trouble!