by Michael Miller

Have you ever heard the statistic that 70% of organizational change efforts fail? It turns out that this number is a very rough estimate, but it still points to a deeper truth: Change is hard. Change efforts are often met with resistance and not as successful as organizations would like them to be.

The question is: Why?

New research published in the Academy of Management Journal suggests it’s because leaders keep doubling down on the same old playbook that led to this dismal success rate in the first place. They “create urgency” and push people to “jump into the new paradigm.” It’s a playbook that ignores some basic principles of how the brain responds to change and uncertainty. As a result, leaders often end up exacerbating employee’s fears and increasing resistance, when they intend to do the opposite. Let’s take a look at the typical change management process and discuss a simple, actionable solution to make change efforts more successful with emotional intelligence.

What’s wrong with the typical change management process?

Common wisdom says that successful change efforts depend on visionary leadership. Leaders must make the case for the changes by explaining what’s wrong with the current situation and how the changes will lead to a better and brighter future.

And if there’s still resistance?

Make it even clearer why the changes are needed! Bring charts, graphs, and experts! Make an unassailable case. Use data to emphasize what is good about the changes, and what’s bad about the current reality. But often, this only serves to entrench resistance even more, which has perplexed leaders for decades and continues to stump them today. So why doesn’t this strategy work?

It’s pretty simple: The brain doesn’t care about facts; it cares about safety and belonging. And when employees perceive change as a threat, and leaders never address those fears, everyone gets stuck in a vicious cycle of fear and resistance. Breaking free of this cycle starts with leaders understanding how the brain typically responds to change, uncertainty and stress, and using their emotional intelligence to address those fears with compassion and honesty.

Consider this common situation: Someone expresses a doubt (which reveals an emotional need). You can imagine the prototypical, quantitatively oriented corporate leader’s response: “You’re not listening. Look at the facts, it’s clear that we have to change.” This reliance of facts fails to address another important fact: People are not just rational.

How the brain responds to uncertainty

The human brain is hardwired to dislike uncertainty, to equate it with danger. Research has found that people would literally rather know something bad is definitely going to happen than face uncertainty. And change is a movement into uncertainty.

You can scream from the mountaintop that the change is for the better, but faced with uncertainty, many people experience stress. And the typical stress response blocks the exact type of higher level cognitive processes – like empathic and analytical thinking – that is needed to embrace change. Around and around we go. Leaders keep making an argument that emphasizes the change and the factual reasons for it, which only reinforces employee’s fears and the emotional imperative to resist it.

An effective solution is surprisingly simple, per the research at Harvard Business Review: leaders should emphasize continuity, or what will stay the same, in conjunction with the vision for change.

How to make change efforts more successful with emotional intelligence

Two studies reported in Harvard Business Review found that organizational change efforts were found to be more successful when leadership emphasized not only the vision of change but also a vision of continuity, or what will stay the same.

In one study, researchers surveyed employees and their supervisors from organizations that announced organizational change plans – relocations, expansions, reorganizations, etc. In the second study, they tested the same idea in a lab setting with business school students and announced changes to the curriculum, in order to be able to prove causality.

Both studies reached the same conclusions:

When leaders stressed continuity – “how what is central to ‘who we are’ as an organization will be preserved, despite the uncertainty and changes on the horizon” – they were more effective at building support.

And the effects were stronger when uncertainty about the change was higher.

In today’s environment of unprecedented uncertainty, emotionally intelligent leadership is needed more than ever. Leaders ignore emotions at their own peril. Six Seconds likes to say, “Emotions drive people, and people drive performance.” It’s just as true when you replace “performance” with “change”:

“Emotions drive people, and people drive change.” For better or worse.

A framework for people-centered change

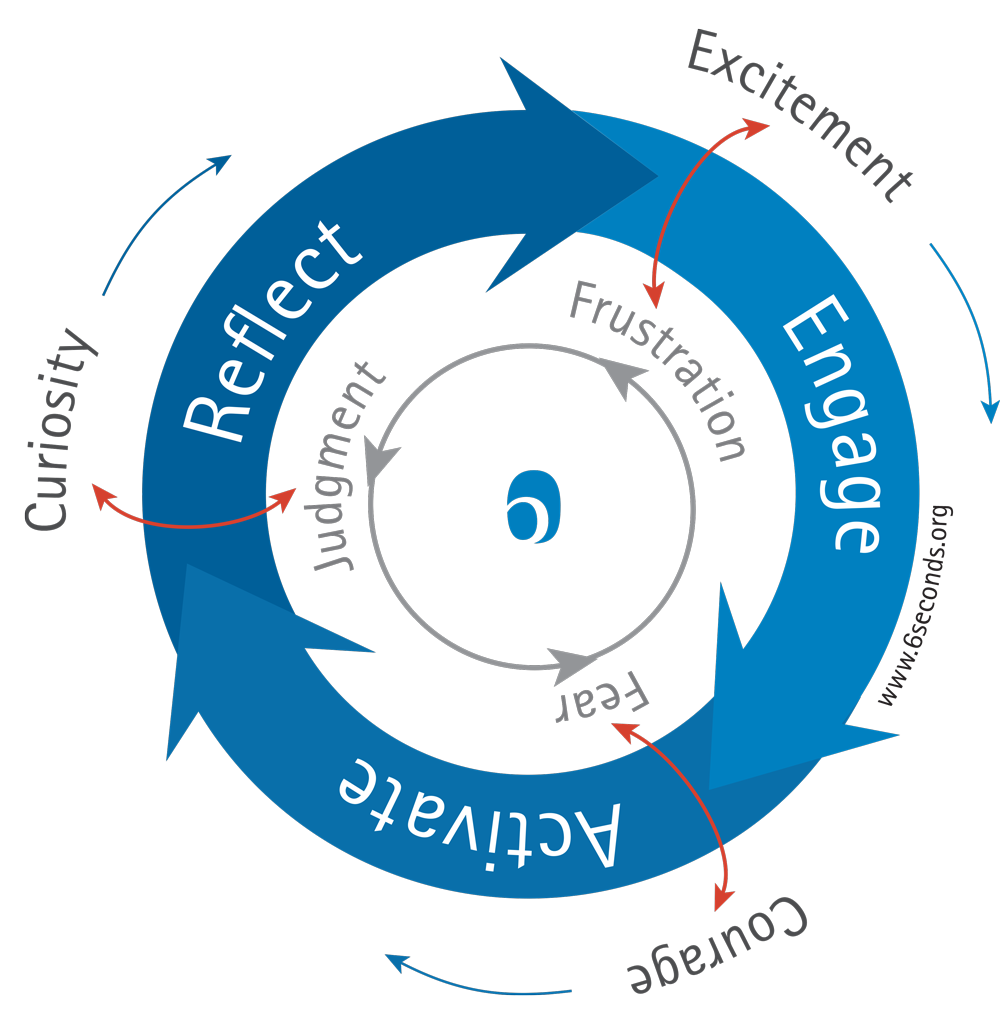

Six Seconds’ Change MAP provides a framework for organizational, team, and individual transformation. Integrating the latest research on change, it’s a process that puts people at the center of change and emphasizes bringing them on board and turning change into a learning process.

The inner grey ring is the “Cycle of Resistance” – feelings that block change. The outer ring is the “Cycle of Engagement” – feelings that fuel change. The red arrows are the transitions — the work that creates the energy for the flywheel to spin.

Imagine if leaders spent as much energy “bringing people on board” as they do “creating urgency” and “making the case.”

What would that look like?

For more on Six Seconds’ Change MAP and its uses for learning & development and change management, check out this article.

And to see Six Seconds’ tools and methods in action, including the Change MAP, check out the case study library – real-life examples from organizations around the world of emotional intelligence increasing performance and bottom line results.

♦

You may also like…

- Pursue Noble Goals in the Six Seconds Model of EQ - July 29, 2023

- Increase Empathy in the Six Seconds Model of EQ - July 26, 2023

- Exercise Optimism - July 24, 2023

Hi, very informative article, thank you for sharing, i definitely going to use all the advice, my son is 14 years old, a very good footballer but he limited himself so much because of fear to lose or to be blamed or to be injured and so more, it’s very frustrating for him, for the coach but also for me, hopefully this article will help us. Be blessed.

Michael, great article. The emphasis on “are employees fears being addressed” is so needed.

Many leaders are so ‘project munded’ to deliver results and their own goals. They don’t think/realize that the reason improvements aren’t sustained is that they are not focusing on bringing ’employees along’.